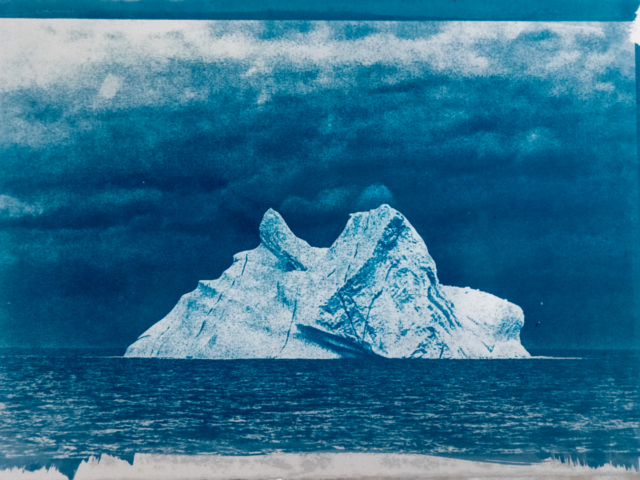

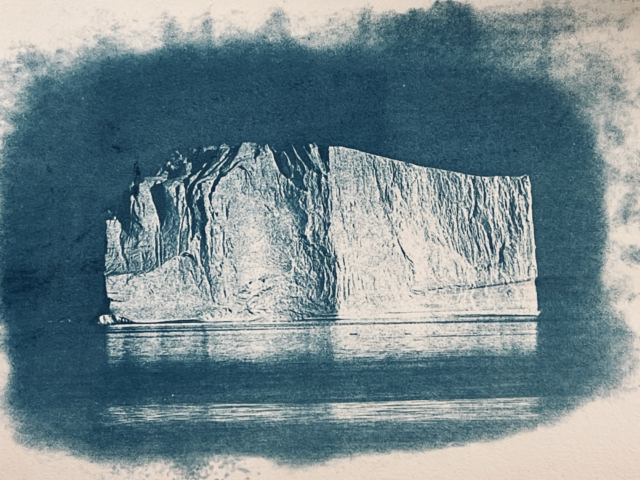

In 2019 I had my first exhibition of cyanotypes of the Arctic in Norway. They were properly made in a professional dark room in Seattle. The results were perfect.

Once I moved to the Arctic, I stopped making cyanotypes. I lacked a darkroom, a printer to print film — any of the things I thought I needed. This froze me in place for six years. Suddenly one day I asked myself why they needed to be perfect. Was there anything about life that is perfect?

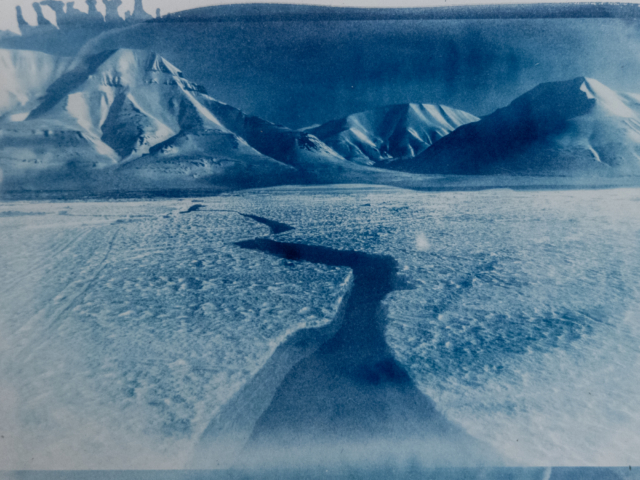

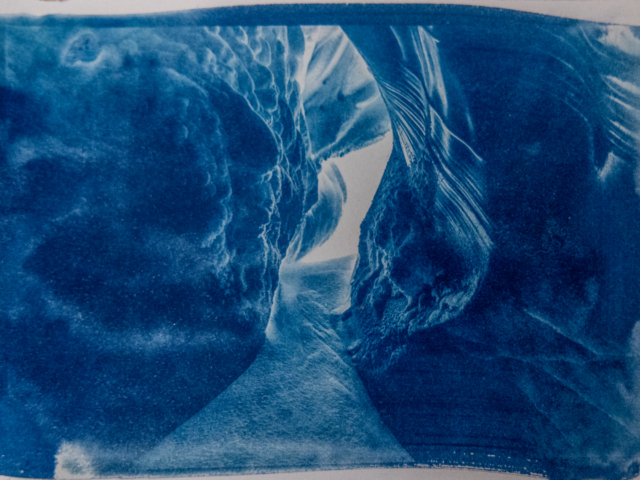

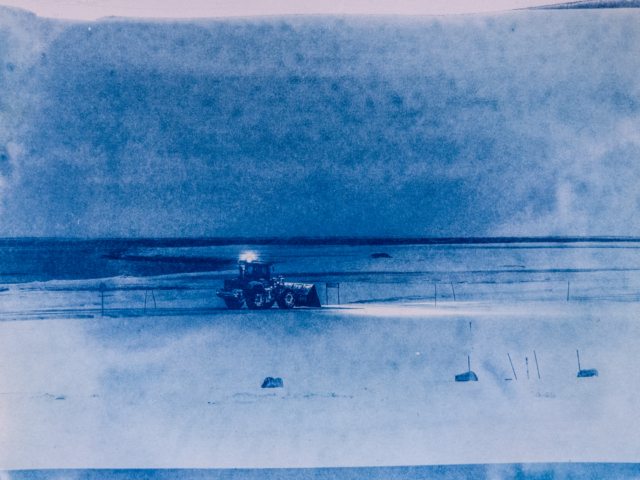

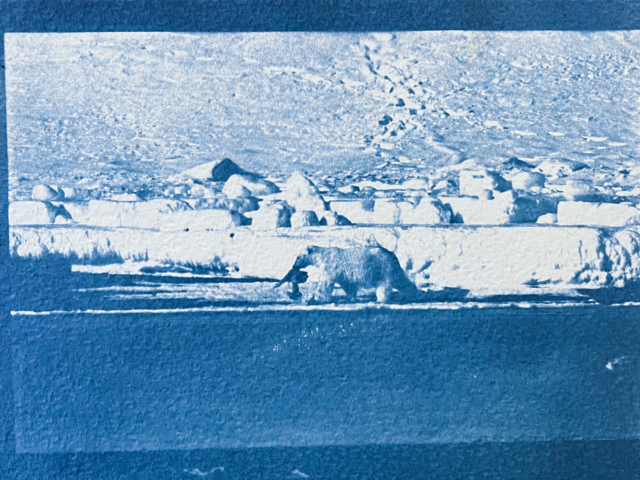

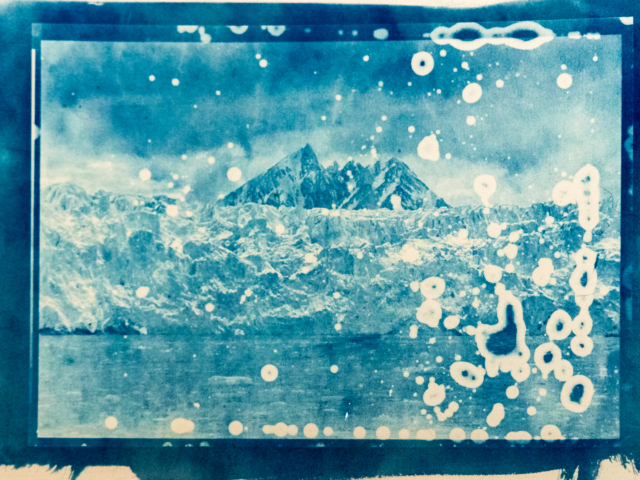

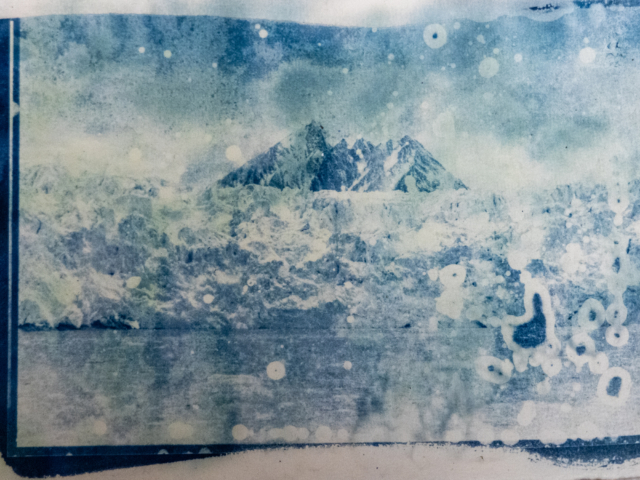

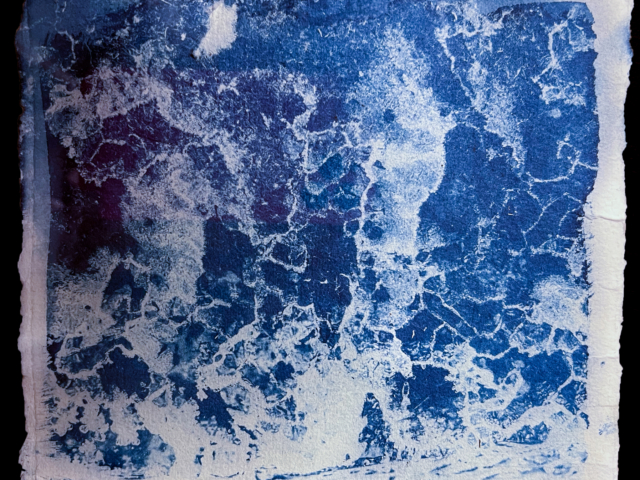

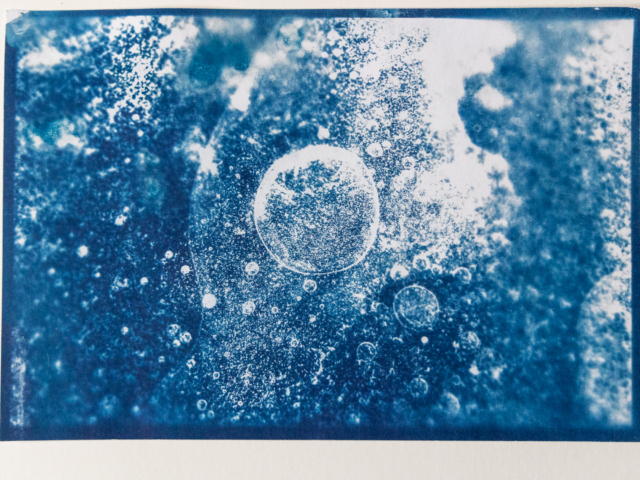

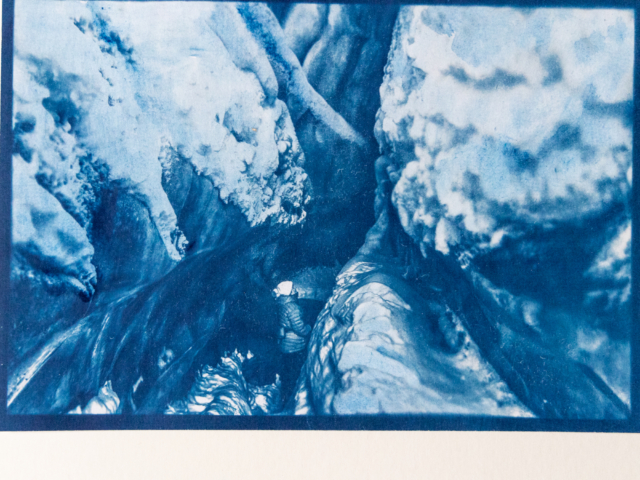

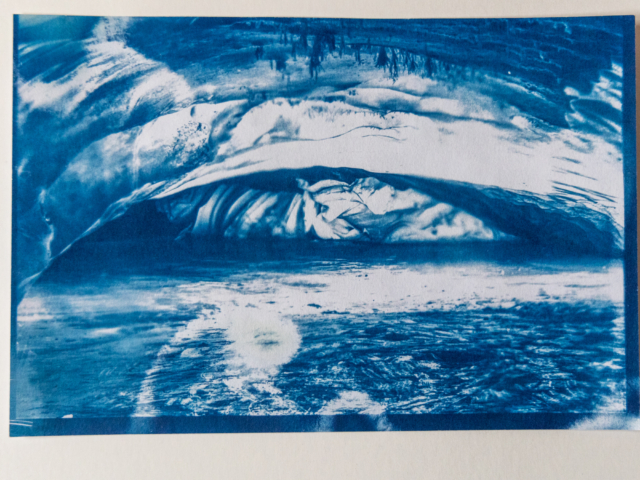

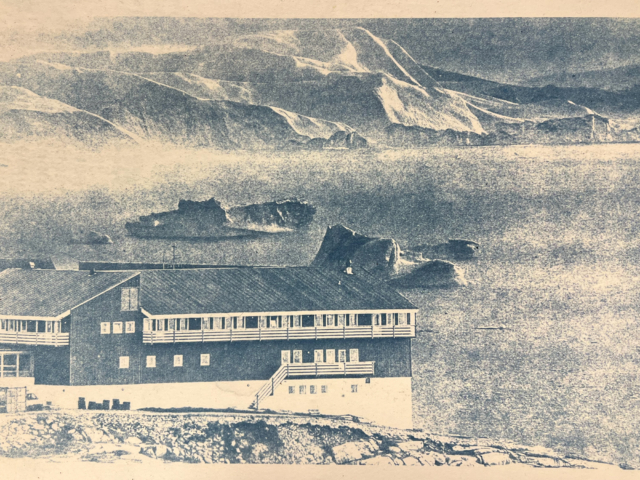

I began to make cyanotypes again. I used the chemicals I had, which were years old. I learned to make paper negatives with an office copier. I used whatever paper I had, and if an image didn’t work out, I would reuse the back, or if it was too light, superimpose a new image on top of the old. I processed them in the Arctic sunlight on board ships, on beaches, near rivers. Where ever I happened to be. I washed them in glacier runoff and sea water, noting the changes. I learned what were the Exposure limits of slanting Artcic sunlight (five hours).

None of these works were perfect. But they were alive in ways the previous cyanotypes were not. These were images of the Arctic I live in. Blue and white and often damaged by human intervention and climate change. And yet deeply beautiful for all of that.