I was in Seattle when corona broke out. My plan was to stay for a month, visit friends and family, and sell my condo. When I left Svalbard for Seattle there was merely a whisper of this new disease in China, and that people in Italy were ill. Two weeks later everything changed. Two weeks later I returned to Seattle from visiting a friend in Kansas, and the first case of the coronavirus killed a man less than ten miles from my home. Then suddenly fifty people were sick, one hundred people. Seattle shut down. International flights were cancelled. Then came the news that Norway was closing its borders.

Friends promised me a place to quarantine in Norway, if I could make it in time. With terror and uncertainty in my heart, I left the US. Icelandair was the only international airline still flying from Seattle. The plane normally carries 269 people. There were only 15 of us. I changed planes in Keflavik without incident. In Gardermoen, young men in combat gear with weapons separated us into two lines: Norwegian and non-Norwegian. I felt like I was in a movie, and not one that ends well. The young man who interviewed me wasn’t sure what to do since I live in Svalbard, which has a special status. But his officer said that as long as I had a Norwegian family willing to be responsible for me, they would let me in. I had two weeks quarantine, and ended up staying in Grimsbu for three. I lived on the top floor of a farmhouse in looking out over fields white with snow toward mountains white with snow. It was beautiful. It was neither home, nor home.

I made a rule for myself. Every day, I would paint one painting. It was the only way to keep my emotions at bay as I read the  increasingly terrible news around the world. As my son in the US sickened with corona, and then recovered, I could not think for fear. Painting was what I did to manage my fear. I see that work now as a kind of automatic painting, like the automatic writing done by 19th century mediums. They are the kind of thing a child might do. I let my instincts direct my hands, and for three weeks, tried to stay calm.

increasingly terrible news around the world. As my son in the US sickened with corona, and then recovered, I could not think for fear. Painting was what I did to manage my fear. I see that work now as a kind of automatic painting, like the automatic writing done by 19th century mediums. They are the kind of thing a child might do. I let my instincts direct my hands, and for three weeks, tried to stay calm.

When I was able to fly back to Svalbard, I was fortunate to have a perfectly clear day. As we passed Bjørnøya I saw patches of ice, island-sized surrounded by dots of ice. So much ice. In places it looked like the milky way. In others, it spiraled like hurricanes. Amazing. Beautiful. Unexpected. As we neared Svalbard the ice became a sheet of white. Then I saw the mountains, and I wept to be home.

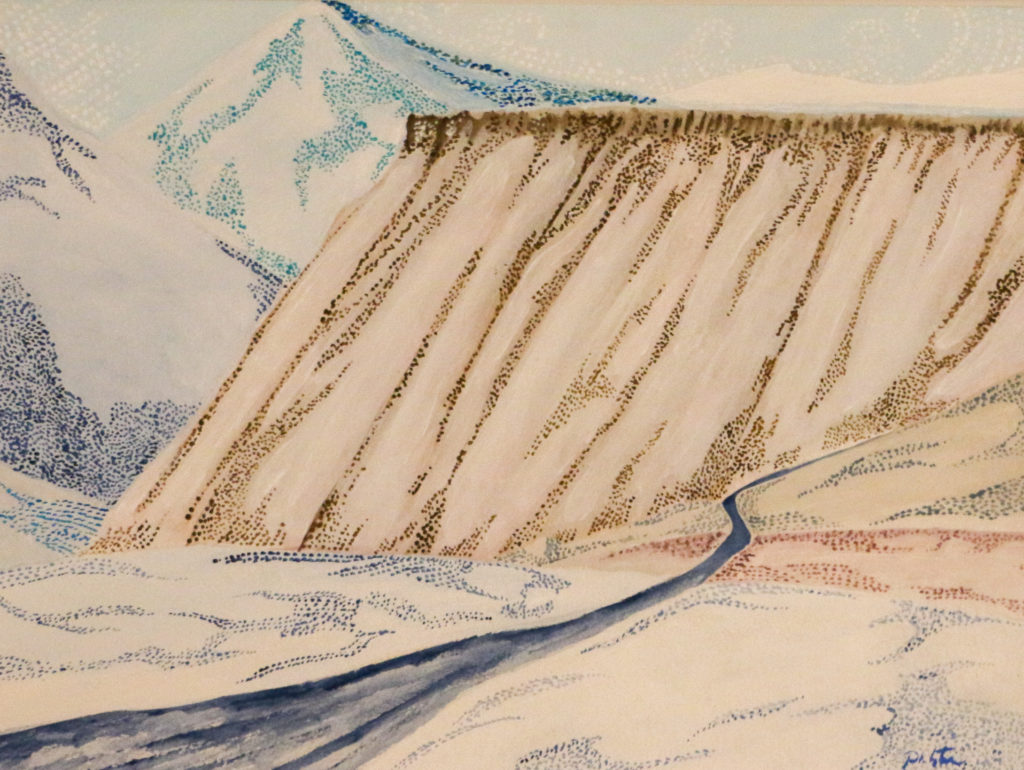

During my second quarantine in Longyearbyen I painted in my studio every day. Seeing the drift ice cracked something open in me, and I experimented with painting small dots of color. I didn’t think of it as pointillism. If you look around in Svalbard, the entire landscape is small dots. This comes from the barren, stony hills. A light snowfall, and the mountains are speckled with white. Svalbard is a true pointillist landscape.

During my second quarantine in Longyearbyen I painted in my studio every day. Seeing the drift ice cracked something open in me, and I experimented with painting small dots of color. I didn’t think of it as pointillism. If you look around in Svalbard, the entire landscape is small dots. This comes from the barren, stony hills. A light snowfall, and the mountains are speckled with white. Svalbard is a true pointillist landscape.

But it was the drift ice that drew me in. I began to paint tests on water color paper. I tested shades of color, shapes of dots, and finally, I painted larger paintings. One meter tall. I realized that what I wanted to do was to fill a room with paintings of drift ice. I wanted people to see what I saw. To really look at it.

I had a September show at Galleri Svalbard. Since I could not do what I had originally planned, which was more cyanotypes, I decided to paint 15, maybe 20 meters of drift ice. I wanted the image to have a narrative, although I wasn’t sure what that meant yet. My studio is not big enough to paint ten or twenty or even five meters at a time. I can at most paint three. So my challenge lay in keeping the full 20 meters in my mind. I had to think about how I wanted the image to build. What would be the flow.

I had a September show at Galleri Svalbard. Since I could not do what I had originally planned, which was more cyanotypes, I decided to paint 15, maybe 20 meters of drift ice. I wanted the image to have a narrative, although I wasn’t sure what that meant yet. My studio is not big enough to paint ten or twenty or even five meters at a time. I can at most paint three. So my challenge lay in keeping the full 20 meters in my mind. I had to think about how I wanted the image to build. What would be the flow.

I painted two five meter by one meter canvasses and one ten meter by one meter canvas. I began painting in May, and finished painting in September when I was able to lay out all the canvases on the exhibition space floor and correct technical and transitional errors.

Of course Drift Ice: Loss and Change is about climate change. Climate change doesn’t stop because we are busy with corona. Climate change doesn’t stop because there is political upheaval across the globe. Climate change is a process. It is ongoing. It is here. Drift ice may become a thing of the past. Sea ice is disappearing. Glaciers are melting. None of this stops simply because humanity is looking elsewhere.

Of course Drift Ice: Loss and Change is about climate change. Climate change doesn’t stop because we are busy with corona. Climate change doesn’t stop because there is political upheaval across the globe. Climate change is a process. It is ongoing. It is here. Drift ice may become a thing of the past. Sea ice is disappearing. Glaciers are melting. None of this stops simply because humanity is looking elsewhere.

But the paintings are also about corona. As of today, September 21, 2020 there are 965,328 people dead from coronavirus.That is such a large number, it means nothing. And yet the grief and pain inherent in that figure surely rises up to the heavens. So many more are sick. Untold numbers will suffer post-illness consequences from liver, brain, kidney damage. We don’t know yet how this will affect future generations. This is a huge loss, and yet we are changing to absorb it.

Finally, this painting is my own personal exploration of how I got to where I am. How did I, a middle-class, middle-aged, contented woman end up in Svalbard? It begins with the death of my beloved husband, which was a nuclear blast shattering my life. Rebuilding who I am, step by painful step, is also revealed in these paintings. From the emptiness of the beginning, to the unimaginable end. The title painting, the ten meter long Loss and Change is full of the icons of my life. They are there to be found for those willing to take the time to look.

Loss is painful. Change is hard. We are losing of a way of life we thought was forever. But as I have discovered in my own life, with that loss comes the possibility for something new, something as yet unimagined, and I believe that these changes, difficult as they may be, also bring with them hope for a better life.

This installation will be in Galleri Svalbard for the months of September and October. The installation comes with a twenty minute soundtrack that walks the viewer through milestones of climate change, the spread of coronavirus, and my personal relationship with this work.